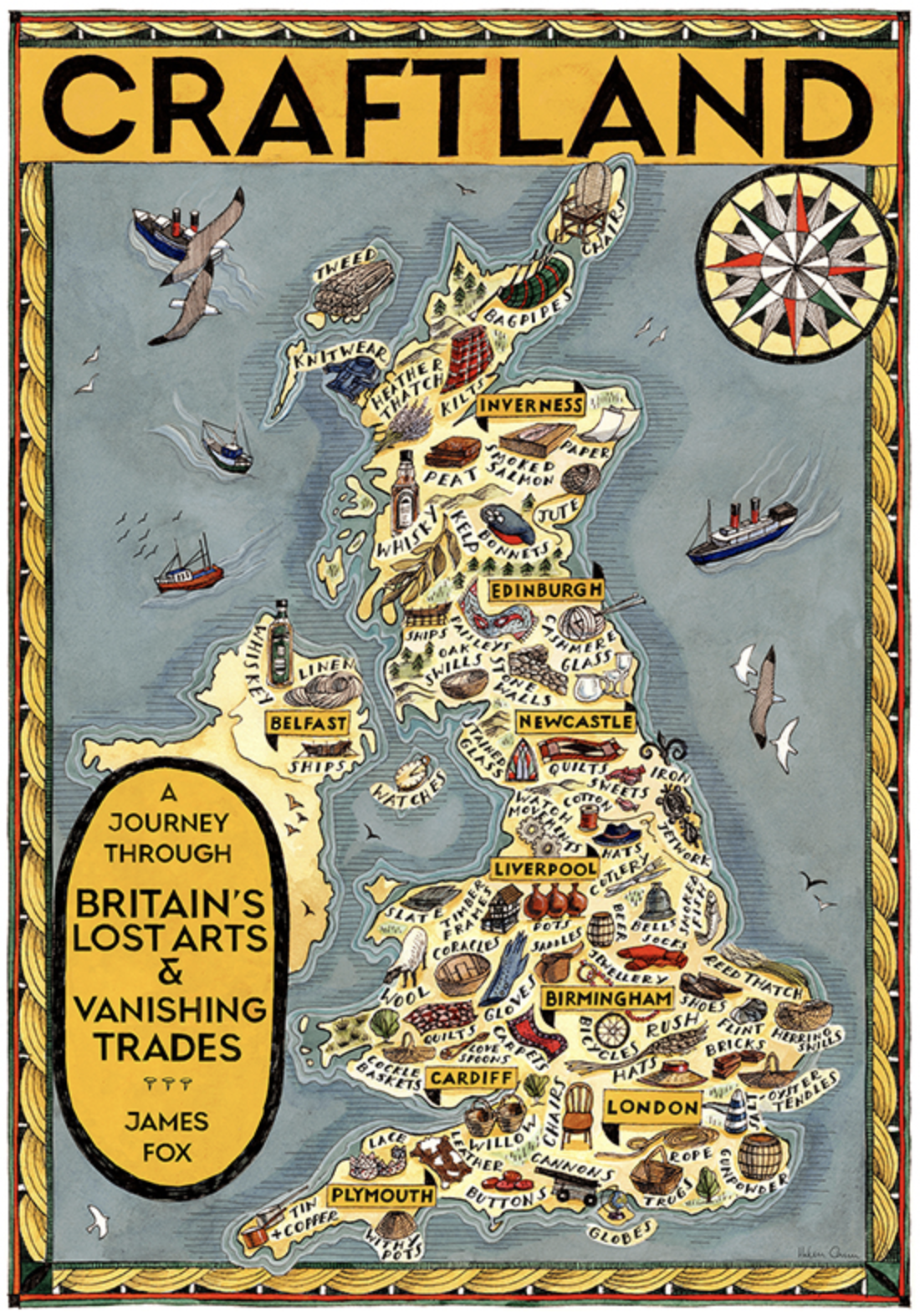

Craftland: A Journey Through Britain's Lost Arts and Vanishing Trades

Alongside my practice, I will be logging my journey into research and exploration that will influence my work and will give context to the themes in which I create work in response to.

As a university student, I found such enjoyment in this part of my course - an opportunity to fully absorb topics and concepts that truly interest me and then reflect on them, and how they are relevant to my practice.

I set my intention to dedicate time to reading and learning about the histories of craft, beginning with a talk at Bath’s Toppings bookstore by James Fox, where he discussed his recently published book ‘Craftland: A Journey Through Britain's Lost Arts and Vanishing Trades’:

Britain has always been a craft land. For generations what we made with our hands defined our identities, built our communities and shaped our regions. Craftland chronicles the vanishing skills and traditions that once governed every aspect of life on these shores.

Travelling the length of Britain, from the Scilly Isles to the Scottish Highlands, James Fox seeks out the country's last remaining master craftspeople. Stepping inside the workshops of blacksmiths and wheelwrights, cutlers and coopers, bell-founders and watchmakers, we glimpse not only our past but another way of life - one that is not yet lost and whose wisdom could shape our future.

For as long as there are humans, there will be craft. It is all around us, hiding in plain sight, enriching even the most modest things. And in this increasingly digital age, it is perhaps more valuable than ever. Craftland is a celebration of that deeply necessary connection between our creative instincts and the material world we inhabit, revealing a richer and more connected way of living.

James discusses the ‘revolution’ in which we are living through right now; a revolution of tech and AI which is already changing the way people live and work and make and even think. This book takes a moment to look back at older ways of working all the ways of making and documenting them before they potentially disappear and partly to see what we might be able to learn from them.

Britain used to be called ‘the workshop of the world’ and it was, at one point, the greatest manufacturing nation, the world had ever known. In the 1880s, this small cluster of islands was producing 43% of the world's manufactured exports. To put that into perspective; China today is only producing 30%.

“Britain was a nation of workshops and studios, masters and apprentices; a society grounded in the act of making things by hand.”

The book follows the story of several craftspeople on their journey of keeping tradition and histories alive through the act of making and continuing the trades that were started by their ancestors.

Craft is that it is not always an easy path, or one with significant financial reward, but it is a way for people to understand the world around them, to connect with people, and connect with histories and heritage. The craftspeople featured in this book are extremely hardworking and dedicated to their practice because they simply can't imagine doing anything else, but the odds against them are growing and they have been growing for decades.

The books finishes with a list of extinct occupations - a lot of jobs that have been replaced by machines and factories, or have simply become redundant in today’s society. James cites the Heritage Crafts’ list of endangered crafts within the UK - as well as crafts that are at risk since the last remaining craftspeople who practice these trades don’t have anyone to transmit the craft skills to the next generation. Without this passing on of knowledge, the craft will become another addition to the list of lost arts and vanishing trades.

It seems here in the UK, there just simply isn’t enough importance put on to creative practices and funding for the arts is consistently being cut and apprenticeships are not being supported. There is no real backing or incentive for artists and makers across the country to make a living from their work.

There are two different kinds of heritage; there's ‘tangible heritage” such as artefacts, monuments, buildings, and sites that have cultural significance and can be seen and touched, and then there's ‘intangible heritage’ the living traditions, skills, and expressions—such as oral traditions, performing arts, festivals, and traditional crafts—that are passed down through generations and recognised by communities as part of their identity. In the UK, we tend to put more value on tangible heritage (UNESCO, National Trust etc) whereas our intangible heritage tends to get neglected.

Within our art histories, we have separated art from craft; art was seen to be made by geniuses, an intellectual profession and they were nearly always white men. Whereas craft was made by women, peasants and made people from other parts of the world and made to seem lesser. Over the last 20 years or so, we are beginning to break down those distinctions and realising there's no distinction between these different practises, it's all about making things.